Chapter 12 — Oborea Among the Islands

or

Bananas and Baguettes

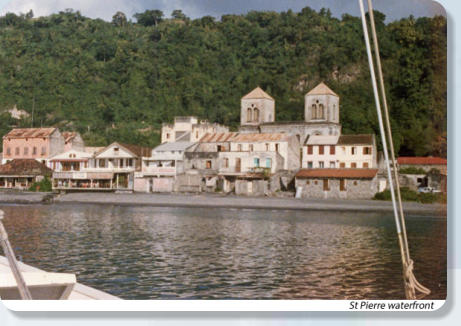

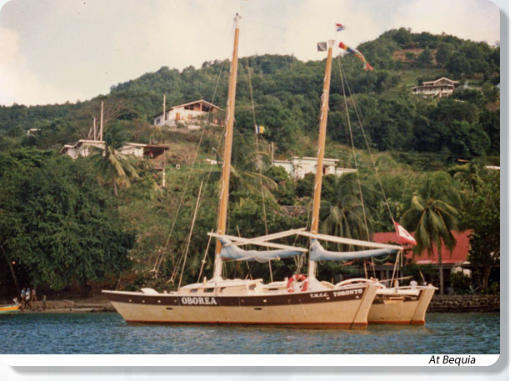

Canouan is another high little island with one small settlement that I passed up to anchor off a steep uninhabited bay on the west side. What is it about charter boats that they need close company? I was the only boat in the quarter mile cove when two charter yachts arrived and anchored right on top of me; one actually started his engine on four separate occasions to avoid drifting into me before he got the idea that he could actually move his anchor further away! Next stop was Bequia, principal island of the Grenadines and the closest to St Vincent. Admiralty Bay is large and well sheltered and I anchored first off the beautiful Princess Margaret Beach near the wreckage of an old fibreglass Wharram half buried in the sand. Later I moved closer to the settlement near two other Wharrams; one from Britain and one from Denmark and both making a living doing day charters between the islands. Bequia was once the boat building centre of the Caribbean, producing schooners and seamen for most of the inter-island commerce. Today they still build neat little double ended sailboats about fourteen to eighteen feet long, and there is a thriving cottage industry producing superb ship models. These are justifiably expensive—all I could afford to do was admire them. Supplies in Bequia are expensive and most of the locals go across to St Vincent to shop. Unfortunately the port of Kingstown is not a good place to take a yacht; two many light fingered wharf rats of the two legged variety—I heard some horror stories. Fortunately there is a great solution—the ferry Friendship Rose which leaves Bequia at six thirty every morning and returns at twelve thirty. She is a decrepit old gaff schooner that makes the ninety minute trip under sail (running her thumping old diesel as necessary to maintain her schedule). Kingstown is small and untidy, but with the remains of some grand old colonial buildings. It has a large and very cheap fruit and vegetable market, and also the huge Geest banana company which ships fruit to Europe. We had been told by other yachts that we could pick up cases of bananas there (about twenty pounds each) for a little over a dollar. Checking it out we found that the technique was to negotiate with the guard at the gate and then wait out of sight round the corner. After a short pause the bananas would appear and money changed hands. As we became loaded down with purchases we returned to Friendship Rose and found a corner to stash them before returning to the fray. Departure time at twelve thirty was like a scene from Somerset Maugham. A human chain (that included the skipper) was loading cement blocks from a truck into the hold. Cases of beer were going into another part of the ship and a deck load of construction materials was going aboard all at the same time. In the middle of all this, passengers were staking out places for their bags and finding comfortable seats among the cargo. On the dockside, among a crowd of hangers-on, kibitzers and longshoremen were vendors selling beer, snacks and even sea-sickness remedies to the passengers. A policeman in spotless white tunic and topee tried to keep order. And all this was against a backdrop of big old stone warehouses and jungle. On the trip back to Bequia a thought occurred to me; we read of ferry disasters in South America or the Orient and we all tut-tut at the flouting of safety regulations, yet here I was with about fifty other passengers and a cargo of cement blocks sailing in an ancient schooner with no life boats or rafts, no life jackets—I did not even see a fire extinguisher—and I was paying two dollars for the privilege! I did not have the money or the time (I was anxious to get to the Virgin Islands where I was to meet friends) to stop at every island on the way north, so I passed up St Vincent and St Lucia and headed directly for Fort de France, Martinique, a passage of about twenty six hours. The gaps between the islands were beats to windward against steep seas (between St Lucia and Martinique they were up to eight feet) and travelling up the lee side of the islands flat calms alternated with sudden squalls. I passed St Lucia in the dark, and although I had fairly recent charts and light lists, I found that ninety percent of the lights in the Caribbean were either extinguished or had different characteristics from those advertised. Off the south coast of Martinique I passed Rocher du Diamant. During the Napoleonic wars a Royal Navy crew somehow manhandled heavy cannons to the top of this five hundred foot sheer rock two miles off the coast, from whence they could harass French shipping heading for Fort de France. The rock was entered in the navy lists as H.M.S.Diamond Rock, and was manned for eighteen months until the crew was forced to surrender (with full military honours) when they ran out of water. I had an escort of Dolphins as I entered Fort de France Bay, and I anchored astern of a British yacht, Sea Raven, that I had last met in Madeira. I found Martinique quite different from the other Caribbean islands I had visited. As an "overseas department" of France the island is considered an extension of the French mainland with the same social services, schools, medical care etc. There are even four lane highways on the island and the stores are those you would find in any French city on the mainland. The people are the best dressed I have seen in the islands; the women in particular seem to have a sense of grace and style, with the latest in French fashion available to them. The island is the birthplace of Marie Rose Josephe de Tascher de la Pagerie, later to become famous as Napoleon's Empress Josephine. The complete integration of the races was very noticeable. On the other islands there is a black population and a white population, but here people came in every shade with no distinction. Lots of good restaurants and the supermarkets stock lots of French products. My only complaints were the size of the French paper money which has to be folded a lot, and the inconveniently long bread. Leaving Fort de France I had the wind abaft the beam for the first time since the Grenadines and had a pleasant trip up the high green coast of Martinique to St Pierre where I anchored in a wide bay in the shadow of Mont Pelée. It is hard to believe today that this sleepy little town was once "The Paris of the Antilles" with wide crowded avenues, a cathedral, a grand theatre, rum factories, horse drawn streetcars, even a stock exchange. All this ended in a few brief moments early in this century when Pelée blew its top, engulfing the whole town in a massive fireball. Twelve ships in the bay burned at anchor, while one that was just getting under way managed to continue, with half the crew dead and the captain severely burned, to bring the news to the outside world. Ashore there was one survivor out of a population of thirty thousand; a prisoner in an underground jail cell who missed the whole thing. Today there is a small museum preserving artefacts such as stacks of sardine cans fused together by the heat, kegs of nails similarly fused and with the keg burned away, twisted and mis- shapen glassware and a great bronze bell from the cathedral folded like clay. Some of the foundations of the old city have been excavated, particularly the theatre, and many of today's small buildings rest on much grander foundations. Over the years there have been attempts to rebuild the town a little farther to the south, but today walking the narrow streets in the rain shadow of Mont Pelée there is still a lingering aura of sadness about the place.