Chapter 11 — Downwind to the Grenadines

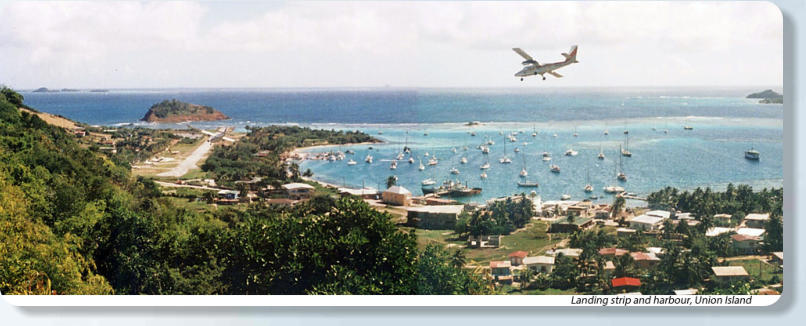

Entry procedures at Barbados had changed since the latest information I had aboard. It was now necessary to take the boat to the Deep Water Harbour (where commercial ships dock) and tie up to a rather high and uncomfortable wall before going ashore to customs. Luckily I did not arrive at the same time as a cruise ship. The formalities were simple and cost fifty Bajan dollars, or about twenty five US dollars. After that I was free to go back and anchor in Carlisle Bay. At first this seems a risky anchorage; a wide bay open for over a thousand miles to the west and off a beach with surf that could be sometimes quite heavy. It is only when the fact sinks in that the wind never blows from anywhere but the east that one starts to feel comfortable about it. (There are a few spaces for visiting yachts in the Careenage, the protected inner harbour of Bridgetown, but it is largely filled with charter and fishing boats). In Carlisle Bay there were half a dozen yachts from overseas anchored off a beach bar called "The Boatyard". This friendly little place caters to the needs of cruising yachts with a dinghy landing pier, phone, car rentals, a laundry in the back, water etc. It is just a short walk from downtown Bridgetown with its department stores, supermarkets and banks. Barbados is not mountainous like most of the islands of the eastern Caribbean. It has low rolling hills and huge sugarcane fields. The west and south coasts are the tourist playgrounds with resort hotels, fast food stores and narrow traffic choked roads. The east coast, open to three thousand miles of Atlantic, is wild and scenic. There is excellent bus service to all parts of the island for the equivalent of fifty cents US. On the busy routes the government run service has been augmented by privately operated mini-buses. These use the same stops and charge the same fare and can be distinguished by their yellow colour and high powered stereo systems. To ride one of them at rush hour with all the passengers singing along to the latest reggae hit is an experience that sticks in the mind! Prices in the supermarkets are high (though not as high as Bermuda or the Bahamas) in particular most of the fruit and vegetables with which we are familiar are imported at high cost. I bought a Caribbean cookbook and learned to use cristophenes and eddoes, papayas and plantains, pomelos and yams. I spent over a month in Barbados; visiting friends ashore, entertaining friends from Canada, and greeting friends I had made in Europe as they arrived from their Atlantic crossing. By mid December the ARC boats started to arrive, the entrants in the Atlantic Rally for Cruisers that had left the Canary Islands on November 27. Soon there were close to a hundred boats in the international anchorage, half a dozen of them catamarans—mostly production Prouts. Ninety percent of the boats were European with only a scattering of US and Canadian yachts. On December 17th Knight Errant arrived, an English monohull I had met in Portugal and with whom I had planned to celebrate Christmas. They had a nine year old daughter aboard and the week leading up to Christmas was taken up in making decorations and baking goodies. On Christmas eve "The Boatyard" held a buffet. It was a novel experience to swim ashore for turkey and ham with sweet potatoes, plantains and jug-jug, followed by Christmas pudding well laced with Barbados rum. Christmas day with the Knights Errant was a pleasant low key family affair. We exchanged hand made gifts, ate too much and drank quite enough. By early January it was time to move on. It cost me another four dollars to leave in harbour and light dues, and then I was off on a ninety mile overnight passage downwind to Union Island in the Grenadines. By next morning I could see a string of steep little mountain peaks poking above the horizon, the tops of this ninety mile island chain, but even with a sun sight I could not positively identify my position. It was not until mid morning that I made out Sail Rock, my target, on the starboard bow. I passed south of the rock, gave Horseshoe Reef a wide berth, and sailed round Palm Island into Clifton Harbour, Union Island. This harbour is on the windward side of the island behind a barrier reef and contrary to what you might expect such an anchorage is often more comfortable than one on the leeward side of a high island. The reef breaks the seas leaving you in calm water and you are exposed to the steady cooling trade winds. On the lee side of the islands you are often plagued by a double swell, waves coming round each end of the island, and the winds funnel down out of the hills in random gusts from any direction so that the boat is always turning. These anchorages are often twenty to forty feet deep, so the boat can cover quite an area while at anchor. Entry was quick and easy with no charge; customs at the post office and immigration at the airstrip. Supplies on this tiny island are limited and expensive. The island is small enough to walk over most of it and in spite of its size it has five little mountain peaks and two settlements. Three or four miles north east of Union Island are the Tobago Cays. These small uninhabited islands are considered the jewels in the crown of the Grenadines—wild and lonely anchorages with beautiful coral reefs. I studied them through the binoculars from Clifton and saw islands very similar to the Bahamas with an absolute forest of masts anchored around them. A couple of miles to leeward two cruise ships were anchored, ferrying their passengers ashore to experience the wild and lonely beauty. I decided to pass up the Tobago Cays and instead headed north for Canouan Heading north through the windward islands proved to be a bit of a trial. The islands trend to the north-northeast and during the winter the trade winds blow from north of east at between twenty and thirty knots. In the gaps between the high islands the wind is often accelerated and you meet waves that have just crossed three thousand miles of Atlantic ocean. The resultant beat to windward has been described by some cruising writers as a refreshing change after the constant downwind sailing in the trades. I can do with less refreshment. When bothered by headwinds in the open ocean I have two strategies, either bring the wind further on the beam and head for somewhere else where conditions will be more favourable, or reef right down and idle along until conditions improve. Here neither of these strategies would help, and I found the only way to get Oborea to windward under these conditions was to put up as much sail as she would stand, grit my teeth and hang on. Thus we travelled north, slamming banging and crashing into the waves, sending everything below flying around the cabin, while on deck we were enveloped in a permanent cloud of flying spray. Anything less and she would just sag away to leeward. In the Windward Islands I drove Oborea harder than I had anywhere else (although I never had all the reefs out of the sails from Union Island to Antigua). I think she took it better than her crew.